Medusa, from beauty to beast and vice versa

Medusa and the gorgons are among the most popular humanoid hybrids in Greek mythology. Their serpentine body, stony gaze and ophidian hair are characteristic features that have allowed them to stand out in the mythical bestiary. However, their familiarity does not prevent us from being unaware of their evolution.

What was Medusa?

Medusa, along with Steno and Euryale, was part of the Gorgons. They were daughters of Ceto and Forcis, primordial gods of the sea, sons of Pontus and Gaea. As daughters of Forcis, they were part of the Forcides together with the three Grayas, the Hesperides and the nymphs Echidna, Toosa and Scylla.

Development

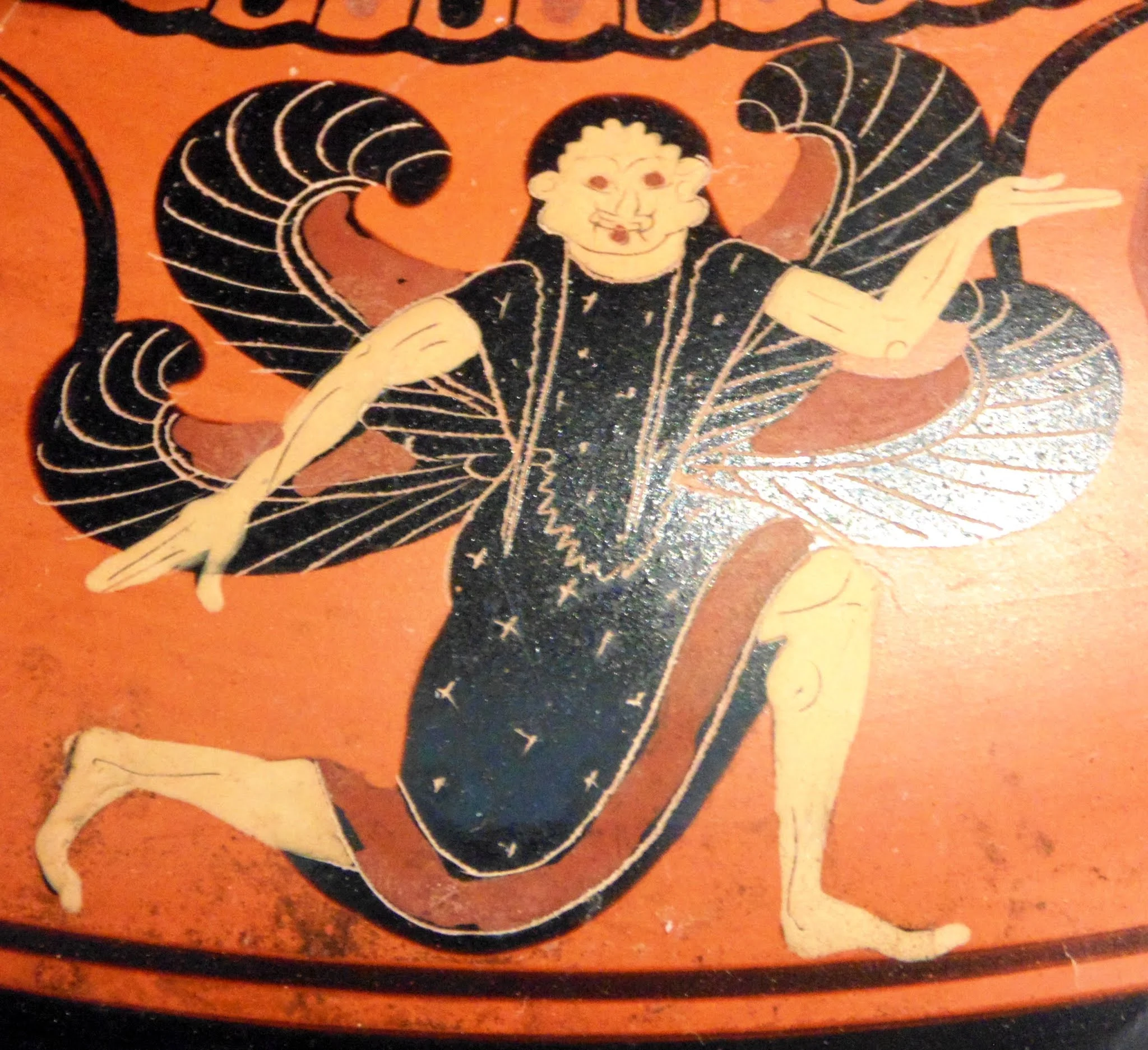

For centuries, their terrifying appearance and piercing eyes characterized them. As with the mermaids, their features developed in literature and art to the point that archaic and classical gorgons had opposite attributes, while maintaining the emphasis on their eyes.

Initially there were no differences between the Gorgons. It was not even certain of their femininity. Only her monstrous face was shown, with large fangs, her tongue out, huge eyes and curly hair that surrounded her head to the point of being mistaken for a beard. It is mentioned in the underworld of Homer's Odyssey as a terrifying head. Not only are there no literary or artistic references to the appearance of its body, but it probably did not even have one. It was widely used in amulets such as the gorgoneion. It was also used as masks without eye holes, such as those found at Tirynthos in the 1930s and housed in the Nauplia Museum. It is possible that they are related to the 6 000 BC masks found at Sesklo. Their face always looked at the viewer, even when their bodies were shown laterally. In those cases, the face had a disproportionate size and no neck. As their body was not defined, they could appear as hypogorgons or gorgons with the body of a bird. This appearance was maintained from the 8th to the 5th centuries BC.

Between the 5th and 2nd centuries B.C., the size of the head is reduced and the neck is acquired. From the 4th century B.C. onwards, it is shown completely in profile and even asleep, with its eyes closed. Her appearance is no longer monstrous and wings appear on her head. This change is often attributed to Pindar's Pythian Ode 12, which mentions the head of the beautiful Medusa in a song to Midas by Acragante.

Even so, it would not yet acquire the serpentine appearance with which the Gorgons, especially Medusa, are known today. Texts describe them with scaly heads, boar-like tusks, bronze hands, wings, protruding tongues, glaring eyes and serpents worn as belts. These snakes could also appear coiled around the neck as a necklace or around the forehead.

Snake hair

Their head was covered by hair, not snakes, although from the 6th century BC onwards these could coil around them or between their hair. On coins, due to manufacturing constraints, the gorgons appeared with hair or with snakes on their heads. Moreover, in a myth told by Pseudo-Apolodorus and Pausanias, they tell how, when he was in the city of Tegea in Attica, Athena gave Hercules a jar with a curl of a gorgon's hair. If it was held three times, the enemy who saw it would flee. On the other hand, Pindar's ode quotes the deadly song of the gorgon, interpreted as the hissing of a serpent.

According to Ovid's Metamorphoses, Poseidon raped Medusa in the temple of Athena, who, enraged, cursed him with her ugliness and snake hair. It is likely that Ovid forced this relationship to explain the children in common that Medusa had with Poseidon, according to Hesiod. Her sisters were also transformed, but their hair was not transformed into snakes, although according to Pseudo-Apolodorus, they were identical to Medusa. They also shared her deadly song and petrifying gaze, as both Pseudo-Apolodorus and Nono of Panopolis indicate in Dionysiacs. In other traditions, Medusa acted similarly to Cassiopeia, boasting of her beauty and comparing herself to the Nereids. Both Medusa and Cassiopeia were punished by Poseidon. The former was stripped of her beauty and the latter was threatened with a sea monster.

Petrifying gaze

Nor was his petrifying gaze constant. In Homer's mention, her gaze was terrifying, but it did not turn to stone. Pseudo-Apolodorus explains, through Hermes, that the gorgon present in the underworld of the Odyssey was Medusa, beheaded by Perseus. When Hercules entered the underworld to take Cerberus away, many souls escaped, but she remained there, where she lost the power to petrify with her gaze. In contrast, Virgil's Aeneid mentions multiple gorgons in the underworld.

According to Pseudo-Apolodorus, looking at her through a mirror or a polished shield would attenuate the effect of her gaze.

Origin and parallels

Historical origin

According to Pausanias, Medusa was a queen of a land near the Tritonid lagoon, who ruled after the death of her father Forcis. She led the Libyans and faced the invading Greek army of Perseus. Although she fought in battle, she died treacherously by night. Amazed by her beauty, Perseus would have kept her head for display in Greece. Supposedly, his head was buried under the market place of Argos. Pausanias would extract this story from Dionysius of Mytilene (2nd century BC).

Parallels

The image of the Gorgons has multiple parallels in the world. Some authors relate it to the Indian Kirtimukkha, while others relate it to the Babylonian demon Humbaba. However, he shares artistic similarities with figures from all over the world. From the terrifying Phobos described in The Shield of Heracles to impossible influences such as Tonatiuh in the Aztec Sun Stone.

The Myth

Artistically, there are common elements even in remote and non-contemporary cultures. If we consider the myth, it is inevitable to think of Perseus, the murderer of Medusa, but this was not originally presented as we know it. Homer mentions both the gorgon and Perseus in the Odyssey, although to the hero only to indicate their kinship. He does not relate them. Hesiod already tells briefly in his Theogony (VIII-VII century B.C.) how Perseus kills Medusa, giving birth to Pegasus and Chrysaor, sons with Poseidon. Pherecydes of Leros (5th century BC) would serve as a source for the Mythological Library (1st-2nd century AD) of Pseudo-Apolodorus, who would combine the various myths of Perseus to create a coherent account. Ovid would add in Metamorphoses (1st century AD) the transformation of Medusa. He would also incorporate the petrification of King Atlas in the mountain range of the same name, something that had already been related earlier by Polyidus with Atlas as a shepherd.

There are several reasons why it is considered that Pseudo-Apolodorus combined several accounts. First, the encounter with Andromeda and Ceto, the sea monster, is usually excluded from the narratives. In addition, the encounter with two trios of Forcides to obtain something turns out to be very similar. It is also confusing that he needs help from the Grayas to find the Hesperides and receive the divine objects, especially after previously having contact with Hermes and Athena. That he gains the ability to fly, invisibility, kibisis, the polished shield and his sword all at once detracts from the heroism of his feat, as it practically feels like a cakewalk to him. Even Heracles was faced with more challenges.

Although Perseus is usually Medusa's executioner, in Euripides' Ion it is said to have been Athena, while another tradition points to Zeus.

The myth of Perseus

|

| Athena, Perseus and Medusa |

Like other heroes, his birth is announced by a prophecy. Acrisius, king of Argos, wishing to have a son, consulted the oracle of Delphi. However, the oracle warned him that his daughter's son would kill him. Therefore, he locked his daughter Danae in a bronze chamber under the open sky in the royal courtyard. Usually, it is Zeus who makes her pregnant with a golden shower, but Preto is also described as the father of Perseus. Not wanting to kill her or enrage the gods, Acrisius locks Danae and Perseus in a chest and throws them into the sea.

During the night, Danae prays for their salvation. She reaches the island of Seriphos, where they are saved by the net of the fisherman Dictis, who will raise Perseus. Polydectes, Dictis' brother, will eventually fall in love with Danae, but Perseus does not trust him. To drive Perseus away, he held a banquet in which he asked for horses for Hippodamia. As Perseus had no horses, he suggested that he bring anything else without refusing. Polydectes asked him for the head of Medusa.

Dismayed by the impossible mission at hand, he met Hermes at one end of the island. After asking him what ailed him, Hermes and Athena directed him to see the Grayas, three sisters (two according to Ovid) of the Gorgons who shared an eye and a tooth, to ask him for the location of the Hesperides, the nymphs who tended Hera's garden. Perseus took away their eye and tooth when they were about to pass them to each other, returning them in exchange for an answer. In some versions he does not give them back, but throws them into the tritonid lagoon.

The Hesperides are the ones who give Perseus the winged sandals, the cap of invisibility of Hades and the kibisis, where he would keep the head. According to Pseudo-Apolodorus, Hermes gave Perseus his characteristic sword. Now equipped, Perseus set out for an undefined place on the shores of Oceanus, although there is a source that mentions the island of Sarpedon. With the help of his polished shield or mirror, Perseus was able to kill Medusa, who fortunately was asleep. From the blood of her neck would be born Pegasus and Chrysaor. Steno and Euryale, Medusa's sisters, pursued Perseus, but he used Hades' cap to escape.

On his way to Seriphos, he flew with the sandals over Ethiopia (not to be confused with the actual country), where he saw Andromeda bound as a sacrifice to the monster Ceto. The sacrifice was intended to appease Poseidon, as he was enraged when Andromeda's mother, Cassiopeia, claimed that her beauty was greater than that of the Nereids. Enamored of Andromeda, Perseus confronted Ceto (not to be confused with the sea goddess and oceanid of the same name). In later accounts he would easily get rid of him by taking advantage of Medusa's petrifying gaze, but in the ancient narratives he kills him by throwing stones at him.

Although they had got rid of the sea monster, the problems did not end, because Phineus (Agenor according to Hyginus) claimed the hand of his niece Andromeda, who had been promised to him. Cassiopeia and Cepheus supported him. Perseus then petrified his opponents with the head of Medusa and returned to Seriphos, where he found his mother and Dictis cornered in the temple by the forces of Polydectes. Again he used the petrification of Medusa.

|

| Perseus petrifying Polydectes |

Finally, she returned to Argos together with Andromeda and Danae and returned their divine gifts. Athena placed Medusa's head on Zeus' shield. The death of Acrisius has minor differences:

- According to Pseudo-Apolodorus, Acrisius fled to Larissa, where king Teutamides ruled, who was holding funeral games for the death of his father. Perseus was participating in the pentathlon and, unintentionally, fatally struck Acrisius with a discus on the foot.

- According to Pausanias, Perseus did not pass through Argos and Acrisius was struck by a hoop.

- In a third account, Preto, brother of Acrisius, had usurped his throne. Perseus petrified Preto and returned the throne to Acrisius, but when Acrisius did not believe that he had killed Medusa, Perseus again removed his head, petrifying him with his eyes.

- According to Sophocles and Hyginus, Perseus killed Acrisius at the funeral games for Polydectes on the island of Seriphos. Repentant and not wanting to succeed him on the throne, he gives the kingdom to Megapentes, son of Preto.

Rebirth

Although the underworld had an influence on Christian hell, the gorgons did not return to it until the ninth Canto of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy and John Milton's Paradise Lost. Then they did so in the guise recognized today.

Sources

- Wilk, S. R. (2000). Medusa: Solving the mystery of the Gorgon. Oxford University Press.

- U. Kenens, ‘Greek Mythography at Work: The Story of Perseus from Pherecydes to Tzetzes’, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 52 (2012), 147-166: http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/ view/12711.

Comments

Post a Comment