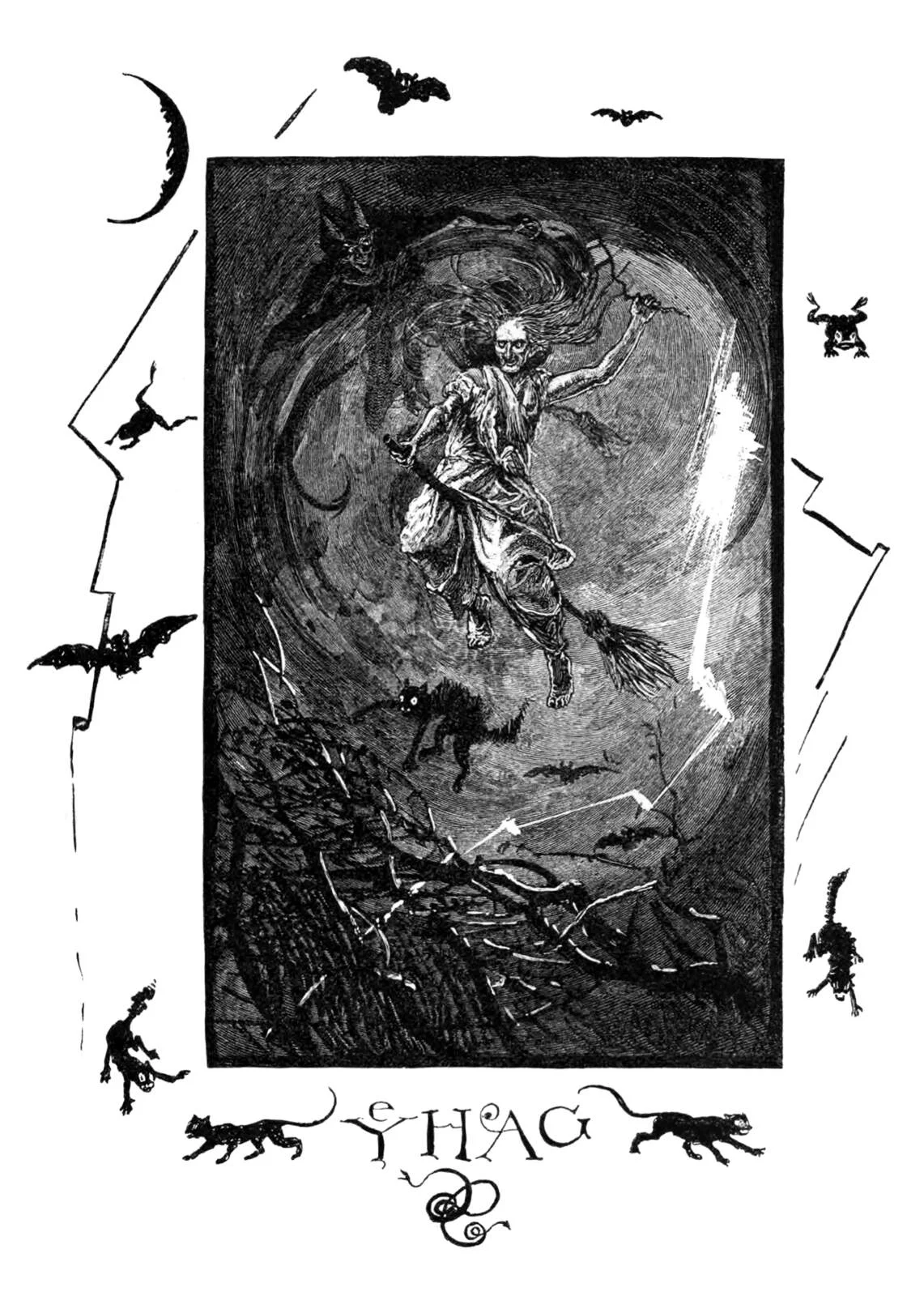

Witches, the women who dominated life and death

They are ugly, old, friends of the devil, a menace to children and master potions and spells. Despite their regional forms, witches are easily recognizable by their common traits. While other fantastic creatures do not transcend their local environment, witches have had the ability to spread across Europe and reach other continents. With this in mind, what is the secret of their success, where did they come from, were they always like this? In this post I will focus on the witches of the texts that, although they may have a basis in the real ones, they do not have to be a completely faithful representation of reality. That is, fiction can exaggerate, embellish or show us only the part that interests them.

From the dawn of history

Mesopotamia

In Akkadian they used the word kaššāptu to refer to witches and kišpū to the art of witchcraft, also called ruḫû and rusû although their meaning had different nuances (in the sense of inflicting evil or subduing, respectively). These came from the Sumerian uš ("witchcraft, saliva, poison"), who also used the word úḫ ("witchcraft, saliva, phlegm"). The witch performed her spell with sputum, just as the god Ea breathed life. Sputum, in analogy to ejaculation, generated life, but also contaminated it and made it sick. Although women and children were the most feared victims of witchcraft, the main victims were men. This could be a bias because the texts are written from the male point of view.

Although in the incantations against witches it is usual that the sex is not specified because the subject does not know who bewitched him, even then it was usually pointed to a woman. This situation seemed to be based on gender roles. While healers tended to be men in the professional sphere, women acted as midwives and created remedies in the home sphere. Moreover, although women could act professionally in cults (qadištu and nadītu), these lost prestige in the middle of the second millennium BCE and became part of the witch stereotype. In some cases they speak of witches (bēl dabābi, bēl dīni, bēl amāti or bēl lemutti), but they are less frequent.

Witches acted on men and gods, reciting spells, by means of food, ointments, baths and gifts. They created figures of the victim with his personal effects to tear him apart, burn him, wall him in, or bury him in a grave, under a washerwoman's mat, or in places where they would be stepped on, such as a bridge, threshold, or intersection. They are sometimes described in opposition to the seven daughters of Anu who bestowed healing waters, drawing water from the sea to bring silence and death through the streets. They were also led by the goddess Kanisurra, close to Ištar and related to the underworld. The penalty for people accused of witchcraft against others was death, but it was a difficult crime to prove. False accusations were also punishable.

Judaism

Despite its religious persecution beginning in the 15th century, the rejection of the use of magic, divination and necromancy in the Bible (Exodus 22:18; Leviticus 19:26 and 20:27; Deuteronomy 18:10-11; 31 and 20:6; 2 Kings 21: 6 and 23:24; Isaiah 8:19 and 19:3; Malachi 3:5) and that witchcraft was one of the evils passed on to women by the watchmen (1 Enoch 1-36), there is one case where it is shown in a positive light: the witch of Endor.

This one appears in 1 Samuel, where Saul loses his reign when he abrogates the laws of the Holy War by not exterminating the Amalekites, keeping some of their animals and sparing the life of his king. Although Saul defended that those animals were to be sacrificed to God, Samuel responded that obedience came first, thus forfeiting divine approval. Then begins a comparison of the actions of Saul and David, who had fled with the Philistines. When the prophet Samuel died, fearing the advance of the Philistines, he sought a divine answer, with no luck. Therefore, although he had expelled the sorcerers and witches from his lands, he went to Endor to seek the services of one who would put him in contact with Samuel. Then the witch, who screams in his presence, transmits to him Samuel's words announcing his imminent death. Otherwise, the rest of the cases are of condemnation. Both women, like Jezebel, and cities, like Nineveh and Babylon, are denounced for witchcraft and sexual sins (2 Kings 9:22; Nahum 3:4).Greece-Rome

In ancient Greece and Rome they had different terms to refer to them according to their occupation, customs or type of magic: those who created potions (Greek: pharmakis or pharmakeutria; Latin: venefica or trivenefica), incantations (Greek: kēlēteira; Latin: cantatrix or praecantrix), prowled cemeteries (Greek: Tombs) or according to the magic used (Greek: perimaktria: one who purifies with magic; telesphoros: one who initiates with magic). They could be referred to by the name of animals (Latin: Striga or Strix), monsters (Latin: Lamia), insults (Latin: Malefica, "evildoer" or Lupula, "prostitute"), euphemisms (Latin: saga, "wise", veteratrix, "veteran" or anus, "old") or by their abilities (Latin: volaticus, "winged, flying"). They could be named with the feminine of the word magic (Greek: goēteutria; Latin: maga, although this term was more general).

In classical stories there are many women who dispose of magic: Circe of The Odyssey; Medea of Argonautica; Simeta of Theocritus' Idyll 2 or Amaryllis of Bucolics; Canidia and Sagana; Enotea of the Satiricon; Erichthon in Pharsalia and Meroe, Pamphylia and Photis in The Golden Ass. However, the distinction between witch, priestess, goddess and monster is blurred, as with Circe and her divine ancestry or Medea's position as priestess of Hecate. Nevertheless, not only do they share elements with witches, such as potions and wands, but in later texts they are the witch paradigm.

Already in this period of history we find several of the most recognizable elements of witches. From the relationship of women with nature through their generative functions and of men with culture, witches were identified with nature. This was their abode, as we can observe in Circe's forest or Medea's remote wild temple of Hecate. Their resources, such as ingredients and tools, also come from it. Thus they gather herbs on the peaks in the middle of the night or use exotic animal ingredients, such as lynx entrails, hyena hump, snake-fed deer marrow, dragon eyes or phoenix ashes used by Erichthon of Lucanus, although they could also use human fluids and fragments. Their association with animals reaches several levels. While Circe had wolves, lions and bears around her house, Apuleius' witches transformed themselves into birds, dogs and flies. They can also compare, resemble or behave like animals. Euripides and Seneca compare Medea's wrath to a bull, a lioness, a tigress and the monsters Scylla and Charybdis. Canidia wore snakes in her hair and Sagana had it like a sea urchin or a furious boar, while Erichthon's voice sounded simultaneously like a dog, a wolf, an owl and a snake. Finally, Canidia and Sagana dig with their nails and tear apart a lamb with their teeth, while Erichthon who eats human corpses and tears them apart with his nails and teeth. This identification with nature, alien to civilization, coincides with the characterization of the Scandinavian trolls, who also inflicted fear. Nevertheless, witches can dominate nature at will.

Furthermore, witches are described as women driven by a lust that men cannot satisfy, causing them impotence. In their rituals they can undress and, instead of going to covens as in later traditions, they flew transformed into birds to stalk their victims. The owl, silent and nocturnal, was a frequent choice. This metamorphosis was maintained in rural beliefs of hybrid monsters with owl parts.

Physically, Greek and Roman witches were different. While the Greeks were young and attractive seductresses who protected their beloved, the Romans were old, frightening and selfish. This difference may be due to the Romans' bad opinion of magic, which was already condemned in the Law of the Twelfth Tables. However, this does not explain why men, except in cases such as Alexander of Abonutico, obtained more positive opinions despite using magic. It may be because Roman women, unlike Greek women, had little power in the religious sphere, so their illegitimate procurement was considered dangerous. Apart from that, they reversed the active-passive position with men, penetrating their domicile or their body, although not through the natural orifices.

As the centuries passed, the witches' wiles became more elaborate and detailed. On the other hand, while the protective spells of the oldest witches invoke the action of the most classical gods such as Themis, Artemis, Zeus, Dice and Helios, the malefic, vengeful or generally harmful actions involve Hecate, Nox, the fury Thysiphone or the Keres. Of all the witches, the Roman strix or striga is the most bestial, a fact that is already revealed by its name, which means "owl" or "owl". This would give rise to beings such as the hag, the strige, the estirge, the shtriga and the strigoi, with more vampiric traits. This association of women with birds of prey related to death could be related to the Egyptian Ba, as with the sirens or harpies.

Christianity

In an attempt to create a Christian family, the church rejected traditional family rituals and sought to warn of the dangers of witches, labeling them as drunks or marriage-breaking prostitutes. It sought to play on its own turf, competing with their services. Baptism, the Eucharist, the sign of the cross, sacramental rituals, and the cults of martyrs and saints were offered as alternatives to traditional rituals and tools. Although rejection continued for centuries, from the 1430s onwards, witch burnings began, which gave rise to many more typical witch characteristics, such as covens with the devil in the form of a billy goat.

Descriptions of the covens appeared in the Formicarius (1435-37) by the theologian Johannes Nider, in Ut magorum et maleficiorum errores manifesti ignorantibus fiant (c. 1436) by the judge Claude Tholosan, the anonymous Errores Gazariorum and the report of the chronicler Johann Frund on the witches of the canton of Valais (1438). However, the decisive work in witch-hunting was the Malleus Maleficarum (1486).

While the elites saw in them the threat of revolt, demonic pacts and necromancy, the people believed that witches flew to their meetings, a phenomenon that the authorities pointed out as a diabolical illusion. That demonic association seems to be an attempt by inquisitors and religious to explain heresies, which they accused as adamism, luciferism and even Judaism. These used to be examples of sympathetic magic, that is, imitation, such as dipping a broom in water to make it rain or sticking a knife in the wall and "milking" the handle to steal milk from the neighbor's cow. Despite this, the authorities interpreted that they always had a demon nearby ready to fulfill their wishes with the slightest gesture. This would be the basis of the family spirit.

The covens would have the function of increasing the magical knowledge of the witches in exchange for sacrifices of limbs, children and loyalty to Satan and his rejection of Christ. One of the gestures of loyalty described in the Errores Gazariorum is the infamous Osculum, a kiss on the devil's anus, and the promise to deliver his limbs to him after death. Around the Alps, where the witch hunts began, the Wild Hunt, traditionally led by Wotan (Odin), would have been composed of generally female spirits who joined the living to their ranks. This belief would be related to the witches who later flew to the covens.

With the discovery of America some of these beliefs would be transferred to the New World. Francisco Nuñez de la Vega (1634-1706) describes that Mexican witches do not follow the devil's indications, although they are his allies, and that they transform into tigers, lions, bulls, flashes of light and balls of fire. In Mexican legends, such as that of the tlacique, and Peruvian legends, they removed their legs and/or eyes to transform themselves, and this moment could be used to get rid of them and get rid of the threat. They also transformed themselves into local animals, such as the turkey in the case of the guajolota. This amputation is common with Lamia, who, unable to close her eyes, plucked them out to rest.

From cult to heresy

One point of view is that witches derived from an ancient matriarchal cult to a primitive goddess of life and death (these aspects would not be opposites, but part of a whole). The iconography of this goddess would be birds and snakes, used individually or together. The details of the cult of this goddess would have remained as vestiges in other religions. For example, the pregnancy of Ereshkigal, goddess of the underworld, in the myth of Inanna's descent into the underworld would allude to this dual nature, the union of life and death. Inanna herself would be another vestige, being goddess of love and war. They would also remain today in the Hindu Deví, manifestation of both more lethal goddesses, such as Kali and Durga, and beneficent ones, such as Parvati.

Sources

- Abusch, T., & Schwemer, D. (Eds.). (2010). Corpus of Mesopotamian anti-witchcraft rituals: Volume one (Vol. 1). Brill.

- Pigott, S. M. (1998). 1 Samuel 28—Saul and the Not So Wicked Witch of Endor. Review & Expositor, 95(3), 435-444.

- Stratton, K. B., & Kalleres, D. S. (Eds.). (2014). Daughters of Hecate: Women and Magic in the Ancient World. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Bailey, M. (1996). The medieval concept of the witches' Sabbath. Exemplaria, 8(2), 419-439.

- Hutton, R. (2014). The Wild Hunt and the Witches' Sabbath. Folklore, 125(2), 161-178.

- Dexter, M. R. (2011). The Monstrous Goddess: The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses into Historic Age Witches and Monsters. Izkustvo & Ideologiya: Ivan Marazov Decet Godini Po-K’sno (Art and Ideology: Festschrift for Ivan Marazov), 390-403.

Comments

Post a Comment