Jötnar, the threat of the Nordic world

In Norse mythology, the Jötnar(1) were the race that inhabited Jötunheimr, a

kingdom confronted by the æsir(2) of Asgard. They are popularly referred to as

giants and gods, confronted until Ragnarök, but this translation is

problematic. Not only does it mask that there were giants among the gods, but

the term "giant" encompasses both the jötunn, the troll, the risi(3) and

the þurs(3). Although these terms come to be synonymized with each other,

doing so leads to problems of congruence in the texts.

The primogenitor

The origin of the jötnar is presented in the Gylfaginning. It tells that in

Ginnungagap, the primordial void where the frost of Nilfheimr and the fiery

sparks of Muspelheimr converged, Ymir arose as a product of the interaction of

these two realms. As he slept, from the sweat of his left armpit a mate was

born and one of his legs sired a son with the other, from whom the frost

giants come.

In this beginning, the keys to the relationship between jötnar and æsir are glimpsed. To begin with, jötnar must procreate by incest or by extraordinary means and are born with multiple heads. In contrast, the æsir may reproduce with members outside their group. In fact, it is common for gods to marry gygjar, but not the other way around, since they have greater rights as they are in a higher hierarchy.

Multiple lands

Unlike Miðgarðr and Ásgarðr, which refer to the central and divine enclosures where humans and gods live, respectively, Jötunheimr refers to the lands of the giants, possibly indicating multiple peripheral locations. Later the term Útgarðr was used to refer to the outer enclosure.One term to confuse them all

Jötnar, trolls, risar and þursar are often translated with the term "giants",

but they have particularities that differentiate them, although sometimes

their usage in the original texts may be interchangeable.

Etymologies and main differences

The term jötunn would come from the Proto-Germanic *etuna, "glutton,

man-eater" if it is assumed to come from the Proto-Indo-European root *ed-,

"to eat". This association is present in Icelandic sources and in Old Norse,

where not only their size is enormous, but also their appetite, greedily

hoarding consumables such as the mead of Suttungr or related to the act of

eating, such as the magic cauldron of Hymir. The jötunn Hræsvelgr means

"devourer of corpses". In addition the jötunn Ægir, king of the seas, is

the host of several banquets of the æsir.

In contrast, the word

risi would have a more neutral sense, coming from the Proto-Germanic *wrisan,

which would derive from the Proto-Indo-European root *uer-, meaning "height".

Its earliest occurrence is in stanza 14 of the scaldic poem Þórsdrápa by

Eilífr Goðrúnarson, in the kenning "wives of risar", referring to the gygjar

Gjálp and Greip, daughters of Geirröðr. The term risi appears later in the

Grottasǫngr of the Codex Regius and in the Codex Trajectinus, referring to

Fenja, Menja and their race. They even appear as bergrisi (berg: "mountain")

on four occasions, but this is a late composition with no mythological basis.

In Snorri Sturluson's Eddas, the risar appear only in the prologue, when Þórr

(evemerized Thor) destroys them as he leaves Troy.

The differences

with the troll and the þurs are more diffuse. The troll, spelled tröll, would

come from the Proto-Germanic *truzlą, meaning "supernatural being, demon,

demon, monster, giant," although it is associated with enchantments and

deceptions. The þurs, meanwhile, comes from Proto-Germanic *þursaz, which

derives from Proto-Indo-European *tur- ("to rotate, turn, turn, roll, move").

It is included in hrímþursar and eldthursar, also called eldjötnar, being the

frost and fire giants, respectively. In addition to giant, it is often

translated as ogre or monster. In the Canterbury runic incantation and the

Sigtuna amulet the infirmity is referred to as þurs, but this relationship is

not attested in Old Norse. They are generally evil, except for Þórir of

Grettis saga chapter 61, who is a hybrid of þurs and human. In the Skírnismál,

the god Freyr sits on Odin's throne and spots a beautiful gýgr named Gerðr. He

then sends his servant Skírnir with his horse and his magic sword. Although at

first he tries on her behalf with gifts, upon his failure, he proceeds to

threaten her. Finally, Gerðr agrees to love Freyr. In these threats, Skírnir

mentions the name of the þurs as a curse, indicating transgression before the

divine will.

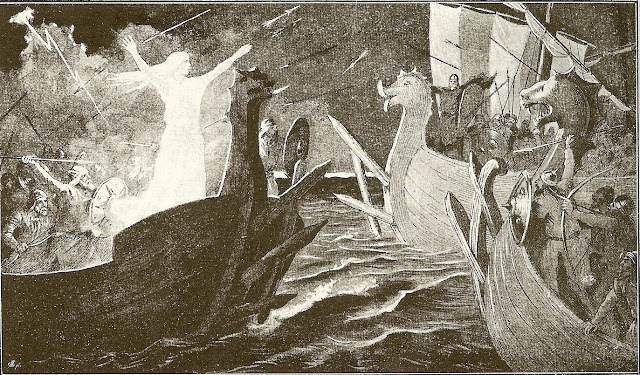

Monstrous and chaotic nature

The nature of the jötnar can be extracted from their use. In the Eddas and in

the Codex Regius, the jötnar are a threat to the æsir, as they try to take

their women, steal their most powerful objects, and engage them in physical

and verbal contests. In a fragment of the Skáldskaparmál, possibly dating from

the ninth century and where Bragi Boddason and a troll discuss, the jötnar,

trolls and völur are listed as devourers of the moon and the cosmos, relating

them to the forces of chaos. An example of this chaotic nature is Loki, son of

a jötunn and an ásynja who produces a monstrous lineage and confronts the æsir

in the ragnarök.

Just as various terms with different meanings are

referred to as "giants," Old Norse or Icelandic translations used jötunn or

jötnar to refer to adversaries or evil beings. In the Gospel of Nicodemus

(Niðrstigningar saga), jötunn is applied to Satan because of his negative

nature and his opposition to the æsir. In Alexandreis (Alexanders saga) by

Gautier de Châtillon, during the Gigantomachy, Typhon is described as jötunn.

In Tundal's Vision (Duggals leizla), there is jötnar in hell. In both Bevis of

Hampton (Bevers saga), Yvain, the lion knight (Ívens saga) and Erec et Enide

(Erex saga) by Chrétien de Troyes, jötnar are mentioned as monsters opposing

humans.

The jötnar are also related to nature. Not only is the world formed from Ymir's body, but Thor's mother Jörð is the personification of the earth; Gjálp urinates on a river and Thor sees its flow increase; Hræsvelgr is in the form of a huge eagle that flaps its wings to form winds in the northern sky; Ægir and his wife Rán personify the sea and its dangers, being called sjórisar ("risar of the sea") or sækonungar ("rulers of the sea") and Skaði is linked to winter and the mountains. When Loki is punished, Skaði is the one who places a snake on him that drips poison, causing him to writhe in pain and cause earthquakes.

More than just size

When translated as giants one might think that this is a constant trait. Ymir

or Útgarða-Loki, who also had troll traits, are examples of this. Yet,

considering the sagas, only in six is it a distinctive feature (4). In fact,

in Maríu saga they appear as Cyclops. What distinguishes them, in addition to

their evil, chaotic nature and enmity with the gods, is their location, since

the stories are located in Scandinavia or northern Europe(5). On the other

hand, the risar refer to foreign giants from other literary traditions, such

as the Philistine Goliath or King Nimrod, who ordered the construction of the

tower of Babel.

Rather than huge and horrible, the jötnar are

predominantly old because of their status as inhabitants of the mythical

world. In the sagas they are characterized by their monstrous appearance, with

deformities, supernumerary heads or limbs, fangs on the snout, missing teeth,

fingers or skin. In contrast, the risar and their descendants are extremely

beautiful.

On the other hand, the jötnar in the sagas have a basic

mentality, contrary to civilization and resorting to violence at the slightest

impulse. In contrast, the risar can even marry human women, something the

jötnar only achieve through abduction. The risar not only assimilate among

men, but can also stand out among them. However, in both Kormáks saga and

Hrólfs saga Gautrekssonar evil risar appear, though without being as basic as

the jötnar. In addition, there are a small number of works where the terms

risar and jötnar are used interchangeably if they are hostile.

Although magic and deception is something that characterizes

trolls, some jötnar are shapeshifters, such as Þjazi and Hræsvelgr, who take

on the form of an eagle; the wolves Sköll and Hati, of jotunn lineage through

their father Fenrir and grandfather Loki, who become trolls before devouring

the Sun and/or the Moon, and, of course, Loki, who is a half-breed, and

transforms into salmon, mare, horsefly, hawk or gýgr.

Through Odin we know that the Jötnar treasure unique knowledge. From Bölþorn, his maternal grandfather, Odin learned a spell related to the hanged. Mímir drinks from the eponymous well beneath one of the roots of the Yggdrasil ash tree that runs through Jötunheimr. As he gains wisdom by doing so, Odin agrees to sacrifice his eye to obtain the right to drink from the spring. He would later obtain his head after a dispute with the Vanir, another group of gods, so Odin used his powers to preserve his head and provide him with advice. Through the Hávamál, it is suggested that Mímir is the maternal uncle who taught him nine spells. Another jötunn related to Odín is Vafþrúðnir, who threatens Odín's reputation with his wit. Such is his wisdom that Frigg, who knows all destinies, warns him not to confront him.

Finally, it should be noted that the status of jötunn is not exclusive. That is, Skaði was a gýgr who went to Asgard to avenge the death of her father, but she was also noted as a goddess of skiing. It is possible that she was formerly a goddess, but was more closely linked to Jötunheimr, especially because of their relationship and longing for the mountains. Gerðr, Freyr's wife, is also listed in the Skáldskaparmál as a goddess. Þorgerðr is even identified as both goddess, gýgr and troll. One explanation would be that the jötnar would have been worshipped in ancient times.

Notes

- Jötunn in masculine singular, gýgr in feminine singular and gygjar in feminine plural.

- Æsir is the name of the main group of gods, although there are also others called Vanir. Áss is its masculine singular form, ásynja in feminine singular and ásynjur in feminine plural.

- The plural of risi and þurs is risar and þursar, respectively.

- Bærings saga, Ála flekks saga, Kirjalax saga, Ectors saga, Sigurðar saga þögla and Tristams saga.

- Landnámabók, Grettis saga, Jökuls þáttr Búasonar, Þorsteins þáttr bœjarmagns, Hversu Nóregr byggðisk, Gautreks saga, Gríms saga loðinkinna, Hálfdanar saga brönufóstra, Hálfdanar saga Eysteinssonar, Ketils saga hœngs, Sörla saga sterka, Völsunga saga, Hrólfs saga Gautrekssonar, Örvar-Odds saga, Hálfdanar saga svarta and Egils saga einhenda ok Ásmundar berserkjabana.

Sources

- Grant, T. (2019). A Problem of Giant Proportions. Gripla, 30, 77-106.

- Hall, A. (2009). ‘Þur sarriþu þursa trutin’: Monster-Fighting and Medicine in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Asclepio: revista de historia de la medicina y de la ciencia, 61(1), 195-218.

- Lindow, J. (2020). Old Norse Mythology. Oxford University Press

-

Hagen, A. L. (2003). The role of the giants in Norse mythology (Doctoral dissertation, University of St Andrews).

Comments

Post a Comment